The Future of Remote Work

Our framework for thinking about the value of remote, in-person, and everything in-between.

The discussion of the future of work post-Covid has now been going on for years, and is nowhere near settled. Some companies are reversing prior decisions to go remote, while others cancel the last of their office space. Debates around the value of remote have continued feverishly, especially since both sides are incentivized to normalize their own point-of-view.

The remote discussion is complex and hard to discuss rationally. As a result, this post includes:

A discussion of why it’s hard to reason about remote

A discussion of why remote work’s positives and negatives

Our framework for reasoning about remote vs. in-office: The experience of remote work, and the market of remote work

Heuristics for what I consider to be the optimal remote stance for different types of companies: Why remote is a strategic advantage to some companies and poison for others

Why It’s Hard to Reason About Remote Work

The discussion of the value of remote versus in-person work is highly nuanced, but if we’ve learned anything from the pandemic that precipitated the remote revolution, a lot of people don’t do nuance at all. Many statements can be true at once:

Remote work is better for parents

Remote work is less intense

Many people are working harder from home than they ever have

Many people spend their days alternating between smoking weed and playing video games

Commuting sucks

In-person businesses operate with more intensity than remote businesses, on average

Mandating office work on Wednesday doesn’t seem eminently unreasonable

Mandating office work on Fridays in July feels like a human rights violation

Doing work from home is great

Managing people from home sucks

Complicating the matter further, even the statements above have their own shades of gray. For example, I prefer working remote in general, but I think that it probably hurts my job performance to be remote too often – and I honestly don’t know where the line of “too often” actually is. I think that high performers generally prefer to be physically present for projects that they care about, but many high performers also have kids, and view their children as their most important projects, not work.

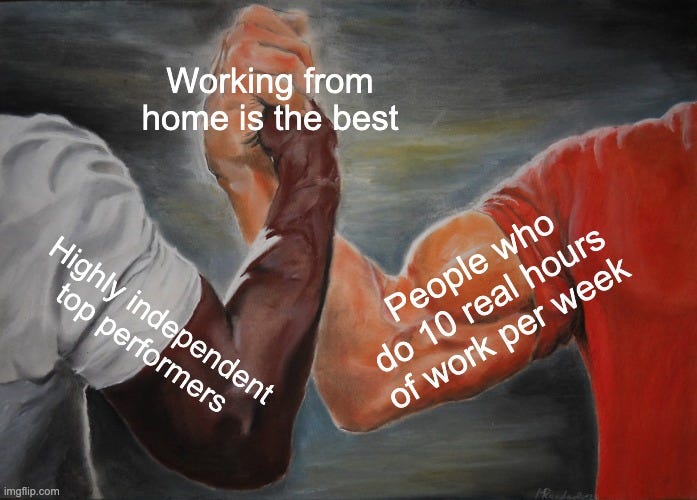

More significantly, people naturally gravitate towards either getting things done, or not getting things done, and remote work allows them to become the fullest versions of themselves. As a result, there is a strict bimodal distribution of remote work advocates:

Driven, independent, highly motivated killers who form the backbone of your company. They tackle new work and make things happen independently with minimal oversight as long as you stay out of their way. Don’t distract them; they’ll get twice as much done if you don’t breath down their necks or throw them off their game.

People who want to hang out, rest-and-vest, and quiet-quit their way through their careers. These people are an anchor that your team has to drag around. If it feels like they’re sitting around at home watching Sportscenter, running errands, and napping, that’s because they are.

In short there really isn’t a good and obvious answer. So let’s break the remote debate into a few components.

A Framework For Thinking About Remote vs In-Office Work

In my opinion there are two competing factors that impact remote work, and these factors have almost nothing to do with one another. The two dynamics are the experience of remote and the marketplace dynamics of remote.

The Experience of Remote

Overall, the experience of remote work is less intense and more independent than the experience of being in-person. This is a good and a bad thing.

Remote work provides a number of benefits. You remove commutes, recovering 30-120 minutes that employees can of course spend however they want.

From what I’ve seen, remote employees spend some of that recovered commute time on work and most on themselves, but as a manager you want this. They’ll be less stressed because they could get a nice haircut or pick up their kids after school. They’ll have more home-cooked meals and exercise regularly. As an employer it’s vital to optimize for your employees as whole people, rather than hours of productive work. Sports teams optimize for their players’ sleep and nutrition; the software engineers on your team are probably not built like pro athletes, but the same principles apply.

Remote work also provides benefits if your team is doing deep work – particularly for engineers and designers, but also for many marketing teams, product managers, finance, and more. People get more done with deep work and it’s just easier to avoid distractions when you’re at home with a comfortable setup rather than getting bothered by Jim from accounting.

The minuses of the remote experience are more significant.

Remote work makes it harder to make fast, difficult decisions. The core of executive decision-making for all of human history has been small groups hashing shit out face-to-face. When it comes time to decide whether to pivot your product, pause the roadmap to take a detour for a big customer, or reorg your company, even small groups tend to get to decisions much faster in person.

The other problem with remote is that it pushes many communications to Zoom, and Zoom is a low-pass filter on positive emotion. It’s easy to delegate tasks or share facts over Zoom – no problem at all. But it’s really hard to communicate the emotional wins. We know that you’ve been working your ass off, we will reward you for it, we care and it made a difference. I know that we lost that deal, but don’t be discouraged – I believe in you and we’ll get them next time. These messages just don’t work well over Zoom; the signal gets flattened by the low-pass filter.

Unfortunately, the same isn’t true about negative communication, which means that Zoom has asymmetric communication downside. It probably feels about half as good to get a raise on Zoom; the low-pass filter tamps it down. But it feels 10x worse when someone uses Zoom to terminate your project, or your employment – the negatives get amplified.

Most significantly, it’s harder for a fully remote team to build the camaraderie necessary to sustain outlier output for a long period of time. In hard moments, the X factor that keeps people striving together is a sense of teamwork and shared purpose. This esprit de corps is almost impossible to build without being physically present with one another. Being in close contact with another human or especially contacting them physically (handshakes, hugs) without getting harmed forms the bedrock of trust. We evolved to trust people that we feel close to, not boxes on a Macbook screen.

Sure, some in-person teams have awful, mercenary cultures and some remote companies share a strong sense of mission. But all else being equal, given two equivalent teams where one is fully remote and another meets in-person weekly, I’d bet my money that most of the time the second team works harder and kicks the first team’s ass.

The Marketplace Dynamics of Remote

The other side of the remote work debate is the market of remote work. Remote can be set up to be cheaper in terms of labor and office space, of course. But even more critically, remote is a key that allows companies to unlock the strongest talent in the world with less dollars or prestige.

There are many companies that need very strong talent, but there are only a few companies in the world that command the highest salaries and prestige. FAANG companies and their dozen-or-so peers aren’t the only ones that need top-tier talent; they’re just the ones who can sustainably pay for it. Every boring enterprise SaaS company that you’ve never heard of has legitimately hard problems – complex workflows, high scale, sophisticated go-to-market motions. These companies make a lot of money and have strong product/market fit, which means that higher performing team members can make a big difference.

In 2019, most companies had almost no chance at hiring top-tier talent away from the likes of Google, Meta, or other equivalents. The only ways to find top-tier talent as a less well-known tech business were:

Train talent yourself (and probably lose it to a stronger company in the future)

Hope that you found the Holy Grail: A brilliant person who also happens to be a terrible interviewer

Without any irony, remote work is changing that. Companies can now pay higher equivalent salaries (say, a solid Bay Area package to someone working in Cambodia). They can provide great lifestyle perks: Live in Montana, ski 4 days a week, and work on interesting problems with other strong team members. These jobs now fully exist.

Sure, maybe you’ll make $30k, $50k, or hell even $100k less per year than you would at the top compensators. This is serious money. But what if it means that you get to play with your kids, spend time with your parents, and live in a National Park? There are people who would take that lifestyle tradeoff, especially as FAANG-equivalent companies and finance (the top compensators in the market) have mandated hybrid work.

Remote has fundamentally shifted the economics of tech hiring. It has encouraged a broader swath of strong companies to pay remote employees more, and in doing so has allowed them to unlock a much longer tail of talent. While many of the world’s top experts may still prefer the intensity of in-person work at the most famous employers, remote allows companies outside of tier 1 employers to potentially access 90th or even 95th percentile talent when before they would’ve been capped at perhaps 75th percentile talent at best.

Who Should Be Remote

Good-But-Not-Great Enterprise Companies

Close collaboration and tight interpersonal bonds make your team more effective. But do you know what also makes your team more effective? Having really smart people.

Think of companies like Instacart, Zillow, Intuit, Atlassian, and Elastic as businesses that are just outside the Hall of Fame, in the Hall of Very Good. They will struggle to compete for talent with tier 1 companies like Meta, Alphabet, or OpenAI – they don’t have the economics to pay as much, and they don’t have the types of explosive growth or world-changing impact (at this moment) that would put them head-and-shoulders above others as places to build a career.

These companies do need talented people, though! Their problems aren’t trivial, they have strong product/market fit, and they’re at scale – more great people really will help them thrive. These aren’t broken-down ZIRP startups that don’t have PMF, they’re real companies with real business models making real money.

The beauty of remote is that it gives companies in the wide zone between bottom feeders and top compensators a huge boon to recruit top talent. As the FAANG companies mandate return-to-office, remote becomes a massive perk for all of the also-rans who can also effectively deploy FAANG-level talent but are a pace behind in terms of resources and prestige.

The ergonomics of remote also work especially well for larger, less-sexy businesses:

Remote companies tend to operate more asynchronously and hire more senior employees – both factors encourage a culture of autonomy, which is key for retaining top talent

More mature companies often have slower growth (especially companies outside of Tier 1), so fast decision-making and rapid PMF evolution are less important

Slower growth often means a higher emphasis on profitability – remote can help here as well, especially if you can get top talent cheaper or cut office space. As a bonus, more profitable companies are more stable, and have less need for the “Ride or Die” startup culture that can only be built in person

Bootstrapped Companies

The equivalent of Horseshoe Theory for software is that the smallest bootstrapped technology companies and the largest enterprise companies actually have similar business dynamics. They both care about free cash flow, efficiency, high gross margins and growth where possible. As a result, both are perfect for remote work like the enterprise companies described above.

Bootstrapped businesses almost always grow slower than venture-backed startups, because the main reason to seek venture funding is to accelerate R&D investment, Sales & Marketing, or both (the other typical reason for raising venture money, for better or worse, is to try to look cool to your friends). Bootstrapped companies grow more gradually and more profitably, again obviating the need for many of the high-intensity benefits of in-person work.

Bootstrapped companies’ lower resources also increase the costs of bad strategic decisions such as poor marketing, bad UI decisions, or sloppy technical architecture. Without surplus funds, it costs you dearly to revert bad calls. This means that highly talented employees are at a premium, and opening up the remote talent pool is one of the best ways to get them as a bootstrapped firm.

Who Should Be In-Person

Early Stage Startups

Early stage startups, particularly of the venture-backed variety, are a lot like being a castaway on a desert island. You don’t have food or water and are going to starve by default. You need to build a boat and sail it to safety before your limited resources run out.

In this situation, it’s very important to optimize for speedy and decisive decision-making. This is not the situation in which you want people kicking back and taking Summer Fridays. In-person and the intensity it brings is a natural fit for early stage companies.

But there’s a much worse situation you can find yourself in as well. Being stuck on a desert island with a shipbuilder, a sailor, and a fisherman is a much better proposition than being stuck with a furniture builder, a schoolteacher, and a software product manager. Team quality is so important that it dominates the probability distribution of success and failure.

As a result, all else being equal I’d try to be in-office or hybrid as a startup – but I actually don’t think that it matters that much. It’s much more important to ensure that your founding team and the first 5-10 people that you hire are the right ones.

Also, at the earliest stages, startups are just about hurling spaghetti at the wall as fast as humanly possible until you get PMF. This requires focused work (which is actually perfect for remote!), but doesn’t require a high volume of the type of no-look passes that in-person work facilitates. Collaboration is dead simple on a 5-person team because you only need to share, like, 3 pieces of information with each other per week. You can share those 3 pieces of information by shouting them across an office, but you can also do it by repeating yourself ad nauseam on a Zoom call or in Slack. So you might as well optimize for team fit and quality above all else.

High-Growth Category Leaders

If you are the best company in your field, or in contention for market leadership, and you are growing fast, then you need to work at least partially in-person.

High growth companies that are in contention for category leadership face two simultaneous challenges: Their product / market fit is typically evolving rapidly, and their team needs to significantly outperform others over a sustained period.

In order to take a dominant market position, companies need to rapidly evolve their products and GTM motions. These companies have to build fast as they rapidly scale up their product, and they need to make sure that their sales and marketing efforts work in harmony with a quickly changing offering. At the same time, they’re usually growing headcount fast which requires extra coordination. Sustained best-in-class execution is a necessity.

My opinion having seen this journey firsthand is that teams should do everything they can to navigate these critical years in-person, ideally all in one location. The hyper growth journey is simultaneously a marathon and a sprint – it requires working with intensity for a long time as the window to win the market opens up. Even more challenging, you have no idea how far you are from the finish line – the best companies may experience 50%+ growth for a decade.

Put simply, high-growth category leaders need to optimize for intensity of work environment. Luckily, these companies also don’t need to worry about the hiring headwinds of in-person as their growth path allows them to recruit the strongest talent who are seeking a seat on the next rocket ship.

A Final Thought – Don’t Bluff, and Don’t Be a Negative Outlier

Some final thoughts on remote work. We’ve seen a number of companies come out with absolute declarations about their remote / office stance, which they then had to double back on. The two classic examples are:

Saying that remote is the future, you’ll be remote forever, working in an office is servitude, etc… and then announcing that you’ll be resuming hybrid work next quarter

Declaring that everyone will be back in the office on X date or will be fired / disciplined in some fashion, and then not following through on the ultimatum

Both of these situations make you and your leadership team lose credibility, and management credibility takes a long time to regain. I urge you to avoid putting yourself in a situation where you declare one policy and later reverse it. Do not punk yourself.

Also, people perceive losses as much more severe than gains. If you let everyone go remote after being in-office, people who are remote proponents may be excited and more inclined to stay at your company. But if you set a firm expectation of remote and are going back to 5-day in-office, get ready for your team to stage a French Revolution reenactment in your cafeteria.

Great read. Another nuance that people miss successful remote companies create lots of opportunities for people to meet in person.

For example, at PostHog we pay for:

- On-person onboarding for new team members

- One or two small team offsites each year

- Co-working and socializing

- One all-company offsite per year

This approach might not scale to larger companies (we're ~35 people and growing atm), but right now we spend less on all of this than we would the equivalent office space in San Fran, and get all benefits you mention RE: hiring etc.